|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Inspirational Messages

Moods

by Fulton J. Sheen

At one time it was

believed that the sun moved about the earth; indeed, it did seem so to the

eye, as we saw it purpling the dawn, and at night "setting like a host in

the flaming monstrance of the West." But now we know that the earth moves

about the sun.

As there were two ways of looking at the relation of

the earth and the sun -- one right and one wrong -- so there are two ways

of looking at the relation between a person and the daily events and

routine cycle of life. Some people live in such a way as to have all their

moods determined by what happens to them in the world. They are sad when

stars take up their encampment on the battlefield of night; and they are

gay in morning's eyes. When there is rain on the cheek of nature, often

tears bedew their own cheeks. What happens at the bargain counter, in the

office or in traffic; the poisoned arrow of sarcasm, the overheard slur

and the whining of children, so often make and mold our moods, that like

chameleons we take on the color of the experience that presently imposes

itself on us. When we allow ourselves to revolve about circumstances, our

feelings become like the seasons, shrinking when some hard service must be

done and fainting in the face of every woe. Even love is reduced to

fickleness, so that the only love songs one hears now on radio and

television are about "how happy we will be' when married; no longer does

one hear the "silver threads among the gold", or the story of how happy

the couple is that said they would be happy with "a girl for you, and a

boy for me." As Edna St. Vincent Millay expressed it:

"I know I am summer to your heart

And not the full four seasons of the year."

The condition of a happy life is to so live the trials and vicissitudes of life do not impose their moods on us. Rather, we become so rooted in peace and inner joy that we communicate them not only to our surroundings, but also to others. Tennyson spoke of such a character "with power on thine own act and on the world." Some radiate cheer and happiness because they already have it within them, just as some seem to have ice on their foreheads, making winter all the year.

The problem is how to possess this inner constancy of peace which makes the depths of our soul calm, even when the surface like the ocean, is ruffled or mixed with storms or cares. The best way is prayer which gives us independence of moods in two ways: first, it exhausts our bad moods, by telling them to God.. The wrong way is to exhaust our bad feelings on human beings, because either they resent them, plan revenge, or they reciprocate by assuming an equally bad mood. Bringing them to God is exhausting them, just like bringing ice to the flame melts the ice. A very false theory in modern psychology is that whenever we feel pent up psychologically, we should give it a physiological outlet -- for example, "forget it; go out and get drunk," or "when the passions are strong, satisfy them."If every son-in-law did this with a mother-in-law who was "moody" with him, the population of the country wourl be reduced by one-teth. It is right to say that the mood must be emptied, but to empty in on ourselves, or on our fellow man, is to get it back either with a hangover or an enslaved condition we cannot break.

The second advantage of prayer is not only to void our bad moods, but to replace them with good feelings. As we pray, the sense of God's presence and law becomes more intimate; instead of wanting to "get even with our enemy," we take on God's attitude toward them, which is loving forgiveness and mercy. We may even reach a point, if we pray enough, where we become unsatisfied until we render good for evil. Gradually we see that it is far sadder to be a wrongdoer than to be the wronged one; the injurer is much more to be pitied than the injured. Eventually we git rid of moods, cultivate a constancy which never retaliates, even as Stephen did, who after the example of Our Lord, forgave those who stoned him. In the strains of life, nothing is as soothing ans as strengthening as the comforting power of prayer.

Moods was provided by the Archbishop Fulton Sheen Archives -- Rochester Diocese of New York

Hound of Heaven

by Francis Thompson

(1859 - 1907)

A failure for so-long; a one-time opium addict; died of tuberculosis. His

poems, mainly religious, are rich in imagery and poetic vision.

I fled Him, down the nights and down the days;

Adown Titanic glooms of chasmed fears,

I pleaded, outlaw-wise,

(For, though I knew His love Who followèd,

Across the margent of the world I fled,

I said to Dawn: Be sudden—to Eve: Be soon;

I tempted all His servitors, but to find

To all swift things for swiftness did I sue;

I sought no more that after which I strayed

"Come then, ye other children, Nature's—share

So it was done:

I was heavy with the even,

But not by that, by that, was eased my human smart.

Nature, poor stepdame, cannot slake my drouth;

Naked I wait Thy love's uplifted stroke!

Yea, faileth now even dream

My freshness spent its wavering shower i' the dust;

I dimly guess what Time in mists confounds;

Yet ever and anon a trumpet sounds

I

Now of that long pursuit

Strange, piteous, futile thing!

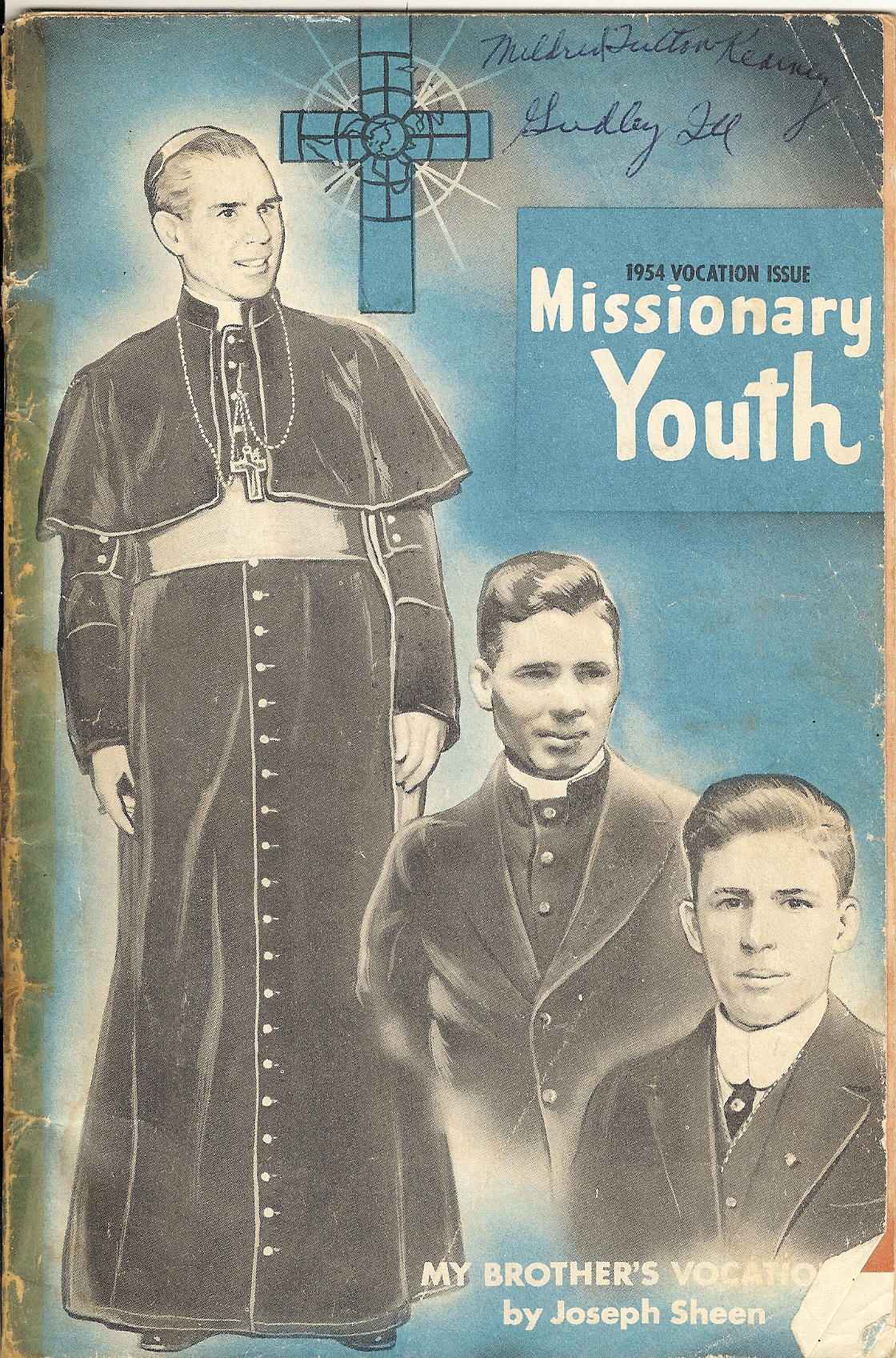

A Stroke of Lightning

Bishop Fulton J. Sheen

Originally

entitled

"Psychology

of

Vocations

for the

Young,"

this

article

was

written

by

the

Bishop

for the

1952

Vocation

Issue.

We

received

so

many

favorable

comments

that

we

thought

it advisable

to

reprint

it along with the

story

of

his

own

vocation.

A

vocation is

as

the

word

implies, a

call,

a

summons

from

God.

This call can come in various ways:

it may

come

with great

suddenness,

like

a

stroke

of lightning; it

can

be progressive

and gradual like

the flowering

of a plant; or it

can

be

habitual in the

sense

that one

can

never

remember

having been without

it.

The

call

does

not

come

to

the

ear,

but to the heart.

One

does

not

"hear"

it as

much

as

he

knows

it.

It

has

the

character

of

the ineffable,

in the

sense

it

can

never

be

described.

If

you

try

to

put it in

words

you

find

you

cannot

express

them.

That

is

why

the

young

are

often

reluctant

to

talk

about

it to

others,

fearful

they

would not

understand.

All

love

is

a

secret

pressed

close

to

the

heart,

and God's

love

more

so

than others.

Then,

too, it is

so very

personal.

Our Lord

said:

".I

call My

sheep

by

name."

This

summons

is

so

immediate

and

so

intimate

that there

is

no

other

way

to describe it than

"God

wants

me,"

and that seems too good

to be

true.

This call

of God produces

two effects

in the soul.

First,

there is a sense

of

emptiness.

The

world

does

not

satisfy.

Soldiers

who

have

been

close

to

death,

and thus

begin

to

appreciate

the

purpose

of

life,

have

their

vocation

made

known to

them

in the

mysterious

sense

of

a deep

void within. This sense

of

emptiness

does-

not

come

from being

jaded

with the

pleasures

of

life

as

much

as

it

is

a

discontent

with

the

world

as the

final

answer

to

the

problem

of

life.

After

parties,

dances

and the

good

times

of

youth,

there

is

still

a restlessness

within.

"This

is

not

what I want."

While

others

are

content

with

such

legitimate

pleasures,

the

youth

with

a vocation

feels

the

tug

of

the

Infinite.

There

is

something

else

he

wants,

and is

almost

afraid to believe

that it can really

be

God

Who

wants

him.

Secondly,

the

vocation

generates

in the

soul

a

desire

to

give

oneself

absolutely

and

completely

to

God;

to

become

a

Divine

Expendable;

to do

anything

God

wants,

whatever

the

cost.

This

is

the

human

side

of

a

vocation.

The

Divine

side

is

the

call

of

God;

the

response

of

the

soul

is

the

human

side.

For

a true

vocation

there

must

absolutely

be the

call

of

God,

for we

must

"be

called

by

God

as

Aaron

was."

The

responses

on

the

part

of

the

young

never

equal

the

summons.

Many

are

called,

but few

respond.

The

response

is

like

an

engagement,

the

espousals

for

which

do

not

take place

until the

vows

are

made.

But this

inner

certitude

that

"I

am

loved

by

God"

is

not

quite

enough,

for

everyone

has

such

a moment.

There

must

also

be

the

desire

to

accept

all the

responsibilities

of

being

loved

by

God,

namely

a

totalitarian

surrender

to

His

Divine

Will;

a

readiness

to

be

used

as

God

sees

fit,

even

as

Dostoevski

said,

"even

to

plug up

a

hole

in the

corner."

What I want becomes

lost

in

what

God

wills

and

as

long

as

this

identity

of

will

perseveres,

there

is

happiness.

The

Hygiene

of

vocation

is

purity.

The

most

disturbing

civil

war

that

can

go on

within

human personality

is

between

the

flesh

lusting

against

the

spirit.

Vocations

are

often

lost

through

the

wind

of

passions,

drowning

the

voice

of

God.

Purity

is

the

sacristan

of a

vocation

and purity

is

reverence

for mystery.

The

mystery

begins

with the

fact

that

as

the

Scripture

says:

"The

body

is

for

the

Lord,"

therefore,

the

body

will

be

used

only

in the

way

God

dictates.

If He

calls

my

soul

to

total

service,

the

body

must

follow

as

a slave.

The

dominating

freedom

over

the

carnal

and

the

temporal

is

the

sign

of

a

great

love.

Love

takes

wings

when

it

is

pure,

otherwise

it is

weighted

down

and

cannot

fly

to

God.

A vocation

then

is

a

falling

in love

with

God,

but it is

a fall

which

is

the

prelude

to a resurrection.

In human

love

there

is

the

meeting

of

two

poverties;

in a

vocation

there

is

a

meeting

of

the proverty

of

self

and

the

riches

of

God.

Such

love

becomes

an

eternal

flame

ignited

from

the

Heavenly

Fire

which

is

God.

The

youth

who

has

a vocation

is

the

illfinite

in

construction.

Originally published in 1952 Vocation Issue of

Missionary Youth

Life Dates | Visitors |

Museum

| Special People |

Holy Mother Mary

St. Mary's Church |

Become a Volunteer | Buy a Book |

Museum Shop

How to Find Us | Our Future |

Our Beginnings | Photo Gallery

| Links | Personal Testimonies

Calendar of Events | Bishop Sheen Quotes |

Inspirational Messages |

Contact

Us | Home